0Comments

PUBLISHED

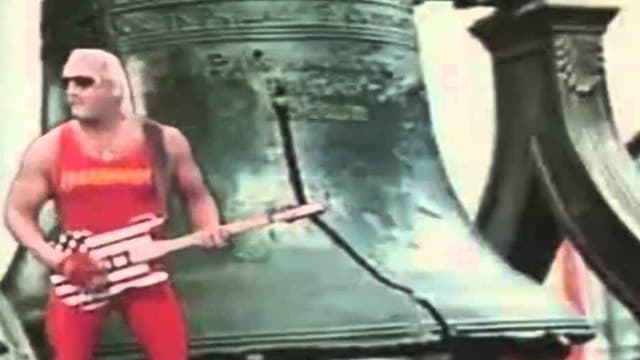

WWE's War on Terror

About the Author

Oumar Saleh

Oumar Saleh is a freelance pop culture writer based in London, England. His work has been published at Passion of the Weiss, Crack and NME among others, as well as being one-thirds of Exit the 36 Chambers - a podcast which convinced the Guardian that he and his co-hosts are "true hip hop heads", whatever that means.

Newest