Just about every Good Omens fan has a story about a copy (or two) that was lent out and never returned as a point of pride. And the book’s struggle to make it to adaptation are nearly as legendary as the book itself, spawning a Gaiman short story (“The Goldfish Pond”) fictionalizing his frustration with the process and a bunch of weird factoids, like the time Robin Williams was pegged for the angel Aziraphale. No adaptation was ever going to live up to that level of hype — in fact, I’d argue that “good enough” was as high a compliment as any adaptation could ever earn.

The production team for the newly-released Amazon/BBC series seemed well aware of that fact, with Gaiman stating in several interviews that his main goal with the show was to make something the late Terry Pratchett would’ve liked. The sincerity shows on all fronts, and that is “good enough” in its own way. I sat down to watch the thing mostly out of obligation, but came away basking in the warmth of familiarity. A very particular type of familiarity, in fact. What I’m saying is that this miniseries is a Livejournal fanfic circa 2006.1

More Like This:

- Why Loving the Source Material Isn’t Enough to Make a Good Movie

- Dating the Primals Of Final Fantasy XIV

- Forrest Gump is a Harem Anime

Our Heroes

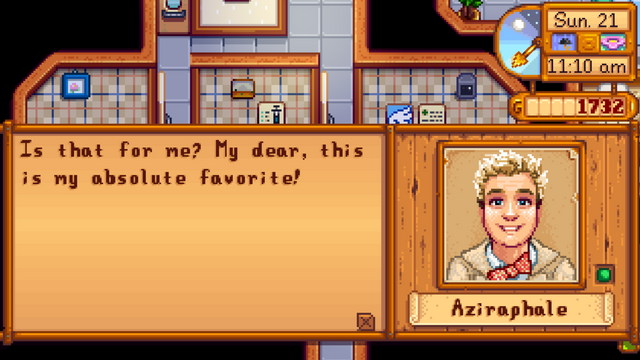

Good Omens the novel is more or less an ensemble piece. The story kicks off with the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley, who decide to team up to avert the oncoming apocalypse because they have much more in common with one another and humanity than their respective sides. They’re soon joined by other characters: misplaced-at-birth Antichrist Adam Young and his friends, “professional descendant” of a prophetic witch Anathema Device, the Witchfinder Army, the forces of Hell, the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, and so on. But the fandom has only ever really had eyes for the angel/demon odd couple.

And like all the fanfic that has come before it, the miniseries reshapes the narrative around Crowley and Aziraphale’s epic centuries-long relationship, with occasional guest spots from other characters at points when the plot simply cannot continue without them. Their witty repartee sparkles with love and care, and their dramatic declarations resound.

The other characters? Well, it’s not that anyone dislikes them. But it shows the series’ priorities when there’s an entire new set of jokes about Crowley’s demonic involvement with cell phones (he invented the selfie, apparently) while Adam’s tomboy friend Pepper is still quoting the same 90s feminism talking points from the book. Or, as my wife continually questioned the TV, “why isn’t Witchfinder Sergeant Shadwell, whose entire schtick is accusing women of being witches and calling his landlady a harlot, hanging around on incel forums?”

Despite a loving reverence of the text, such that sometimes bits of the book’s beautiful prose are bent double so that they can make it into dialogue for recognition’s sake, there wasn’t much more than a cosmetic consideration of how changing the time frame would affect the story.2

It’s Gay(er)

And yea, on the same day that the first fans picked up the first edition copies of the novel, a considerable portion of them agreed that this shit was pretty gay, and it would be best to spend some time pondering the idea of angels being sexless unless they “make an effort.” 6,000 years of ineffably circling one another and comments from basically every other character in the book about how gay Aziraphale and Crowley look, both together and apart, will do that.

Like every self-respecting fanfic, the miniseries set out to make itself even more overtly queer than its source material. The epic story of Crowley and Aziraphale’s relationship, including a bunch of backstory scenes about what they were doing in the intervening 5,889 years before the birth of the Antichrist, is now front and center. Moreover, each of these scenes is driving toward their slow buildup of emotional intimacy, until the clear moment during World War II where they each — independently and without informing one another or even themselves — fell in love with the other one. There’s sappy music and everything.

The script does feel the need to pepper in the phrase “best friends” every so often, in the same way fanfic authors used to put legal disclaimers over their doors to ward off the dread hand of Anne Rice, but it distinguishes itself from queerbaiting juggernauts Supernatural and Sherlock in a key way: everyone and their dog comments on how extremely in love the angel and the demon are, but nobody’s laughing. Nobody’s sputtering about what a preposterous assumption that is. Quite the contrary, on Michael Sheen’s front.3 Meanwhile, the soundtrack helpfully pipes in “You’re My Best Friend,” a love song that John Deacon wrote to his wife, before switching later in the episode to “Somebody to Love.” In case you missed it about the gay angels. Fanfic, for the most part, has never been for subtlety.4 That’s why it’s fucking awesome.

Trope Bingo Card

The majority of what happens in the miniseries is taken from the book. But the devil is in the details, and the show ramps up the drama on a lot of elements… except, weirdly, for the climactic moment in the book where Crowley drives his beloved 1926 Bentley, now in flames, to the site of the apocalyptic showdown because as far as he knows Aziraphale is dead, the only thing that really mattered in this godforsaken world is gone, and he’s going to take all those supernatural bastards down with him. Miniseries Crowley is totally aware Aziraphale is fine, and it’s a bizarre story choice when everything else about their plot is high drama.

The added elements are practically a checklist of fan favorites: Aziraphale sheltering Crowley from the rain with his wing in the Garden of Eden, a decidedly PG version of the many, many kinky things fandom found to do with wings; those aforementioned flashbacks, particularly the stopover in revolutionary France; a newfound level of angst over Crowley’s emergency bottle of holy water so that Aziraphale’s tsundere exterior can visibly crumble, and the expansion of many cameos from Heaven and Hell into characters with multiple appearances.5

But the biggest one of all, the moment that made me sit up on the couch jaw agape, is the trial subplot. No concept has generated more fanfic across countless websites than the question, “what’s going to happen to these two if their respective and decidedly petty sides decide to take retribution?” Followed only narrowly by the second biggest question, “but what’s going to happen when the really for real apocalypse happens?”6 The miniseries might only nod toward the second question in dialogue, but it goes full ham on the first, with a new final fakeout wherein Crowley and Aziraphale are ripped from one another’s sides and taken to their respective employment offices to face trial.

Honestly, the only thing it was missing was Aziraphale dramatically Falling at a key moment so that there can be twenty more chapters of emotional fallout. Instead, all I got was an abject moment of terror before realizing that this wasn’t actually going to lead to a high-budget sequel series that wouldn’t be as good as what fandom can do for itself.

For Fandom’s Sake

But that’s rather the point, isn’t it? The only reason I can make an entire snarky article about fandom traditions is because I loved the Good Omens fandom, almost as much as I loved the book itself. What makes the miniseries as enjoyable as it is is how much passion the crew clearly feels for the material. It’s the same kind of energy that creates good fanfic.

Modern conversations about fandom often revolve around a toxic sense of ownership, a conversation often necessitated because fans used to being the target demographic for a work (cis, heterosexual, white, male ones) have taken to responding with death threats and petitions to remake whole works of media while the rest of us are used to going to our corners to revise our disappointments through fanfiction. And while Neil Gaiman has benefited from that same cultural-majority privilege in that he gets to publish and win awards for his fanfiction rather than be a punchline for it, he does at least grasp what makes it so special.

Good Omens the miniseries is a big old fanfic, and it’s shaped by 30 years of community conversation in the same way as JJ Abram’s mischaracterization of James T Kirk as a meathead jock.7 “Fandom entitlement” is a real thing in the immediacy of modern pop culture and boundary-crossing behaviors taken toward creators, but there is a distinct and unique power that fandom can give the marginalized over older works to reclaim and reshape it over the course of time. Good Omens doesn’t wholly fulfill that potential in the same way as something like Hannibal8 or the She-Ra remake, but at least for me, it managed to be good enough.

1 Footnotes are a requirement when talking about Good Omens. I don’t make the rules.

2 So, that part’s not like good fanfic at all.

3 We will not be dissecting Gaiman’s faffing about how the two characters who apparently present as socially male the entire story – or at least the same gender as one another – and who were cast from the Stock BBC Leading Man Department, do not count as gay; there is not enough time in the day and my queer trans ass is tired.

4 Fanfic is, in fact, frequently for subtlety, and specifically the exploration of nuanced details from the original text in further expanded detail, but that’s not very funny is it?

5 But oddly, not the cottage on the South Downs.

6 It’s a longstanding tradition for fandoms to fill in the opposite emotional need that a piece of media provides; the more lighthearted the original work, the more fans will dig into that unexamined angst, and vice versa.

7 But like, with giving a shit.

8 Drink!